Sunward

Rina daughter of Issa swam into the Speaker’s Cage and looked around at the assembled heads of the Families. She waited for the light and noise to die down as the audience noticed her presence. Temple Square was not far from the hydrothermic vents that brought energy and nourishment to the colony, and she nibbled at the glowing manna stalks waving in the current along the sidewalls while she waited. She turned one eye to examine the left side of the audience, scanning the clusters of conservatives and temple leaders, while the other eye looked calmly forward. On the left, she saw her nemesis Wingren daughter of Beth conferring with her counselors, snouts together—Wingren and her mate Izac, Magister of the Temple, were the most powerful enemies of Rina’s reforms. Rina’s sisters, the key to her reform coalition, dominated the right side of the crowd.

Enough delay. She pulsed her headlights to get their attention. “My people—it is time to free us from the old ways and break the meaningless taboos imposed on us by the Temple. My mother was chosen by the gods to lead us, as my line had from our first days. But we know the gods placed us here for a purpose. We have faithfully tended their machines, but the machines no longer respond as they once did. It is time to face it. The gods are not returning.”

Her echolocation pinpointed the areas of disbelief, mostly on the left, but elsewhere as well. She paused for a moment until the noise died down, then went on.

“We must stop tending the dead machines and look beyond to what the gods would have wanted us to do today. Something has changed, and we must seek further guidance. The Elder Tapes speak of worlds beyond the upper seas, beyond the cap, where the gods came from. We will seek them out.

“Our expeditions have returned with more knowledge of the upper seas, and we have reached the cap. My plan is to drill upward through the ice cap to reach Europa, the fabled Sun and Stars, and old Earth where the gods lived.”

One of Wingren’s cousins pulsed blue and shouted, “It is blasphemy! The cap is taboo! The Tapes tell us to attempt no landings there!”

Rina turned and focused both eyes on him. “I have listened to the Tapes. There are many confusing stories, some of which may be untrue entertainments. Not every word can possibly be true—there are many contradictions, and many words we are guessing at. The Temple commentaries on the stories have been used to justify whatever powerful families wanted for too long. Any further disturbance, and I’ll have the ushers remove you.” The heckler hung back, and the noise from the right side of the crowd died down.

Composing herself, Rina continued. She could see her guards moving into place behind the Temple factions. She looked to the guard leader, who gave her the nod to go ahead.

“Starting now, I am establishing a new Temple to the One True God of the Sun. The gods we knew have abandoned us, and the source of all life is Sunward, toward the hidden Sun, not the gods we have worshipped—whom I have concluded were only human beings like ourselves, who came here from the Earth-under-the-Sun.” The cries of outrage from the Temple families increased as they realized the soldiers had come for them. Struggles broke out, with her soldiers throwing nets over the largest females.

“The Temple and its workshops are forfeit to the new church, and worship will be established under a new priesthood we have selected. Taxes will be levied, and our industries repurposed from frivolous production to create more and better ships. Merchants are hereby required to cede their vessels to the new fleet. All production and trade will be managed to grow our resources for the effort to reach the Sun. There lies our destiny.”

#

Surprisingly few executions had been required to gain compliance. Wingren’s was the first, of course, and the only one she would attend personally.

Wingren was held in a loose net, her struggles weakened by the drugs in her food. Her lights were dim and yellowed. Rina stayed outside the ring of guards and taunted her.

“Your friends are remarkably silent now that you have no power here,” Rina said. “No one will miss you.”

Wingren opened one eye and focused on Rina. “You have won. But the gods will show us who they favor. They will punish you for what you have done.”

Rina had made sure the invited witnesses were not allowed near enough to hear Wingren’s slurred speech. Rina raised her voice to make her message loud and clear to the observers.

“I will go to meet them personally. They will see our loyalty and our devotion to following them, and reward us. They will accept our tribute and give us their blessings. They will restore the machines they left us.”

“I hope you are right, for our people’s sake.” Wingren closed her eye. “But I fear you are wrong, so wrong that you will endanger us all. If you pierce the cap, you may end the world as we know it. I’m asking you not for me or my family, but for all of us—by the gods, consider the chance you are wrong! What harm may come from breaking through the roof of the world?”

Rina laughed and moved back, signaling the guards to begin. They battered Wingren from all sides, her cries mingled with their gruntings. Soon she was still, clouds of blood and foul excretions around her.

The taste of blood and shit in the water lingered—sometimes she thought she could still detect it, these many months later. But she told herself it was a small price to pay for an end to stagnation.

The old Temple families had been sullen, but she released most of them and gave them allowances to keep them under control. By giving out posts in the new Temple hierarchy, she established complete control over the Families—some lesser Families moved up, while Wingren’s family was broken up and driven into the wilds. While females had always been the titular rulers of Sea and Families, rogue males who had failed to join a Family were a powerful wildcard—impulsive and seafaring, explorers and adventurers willing to buck authority and risk their lives for wealth to attract a mate. They ran the ships trading goods between the settlements, which were clustered around the hydrothermic vents. The celibate male priests left behind ran the Temple and wrote the Commentaries that instructed children on how to behave morally, but Izak, their former leader, had not been popular, and his execution was well-received. Most of the old priesthood happily accepted new positions and new doctrine. Rina put them to work rewriting the Commentaries, for the new Age of the Sun she had begun.

Rina’s mate, Joss, stayed near her side during the recovery. His network of unaffiliated males had been key to overturning the power of the Temple—males were considered easily distracted and temperamentally unsuited to the steady and dull work of governance, but they had considerable influence over their mates. It was an open secret among the largely male engineering caste that the drillheads left by the gods were close to worn out, so no new power stations could be built, and the older ones were failing. Joss had brought her the plan to overturn the Temple’s hold on the workshops and reverse their decline before it was too late. His proud crest had turned golden with age and power after she had defeated her rivals, and he came to her the night before the new ship he captained, the Indigo, was to set out for the cap. The ship was the largest ever built, with a record eight flotation chambers and two independent propellers behind. Its batteries held enough power to generate the needed flotation gas and run the propellers for weeks.

“You could still come along,” Joss told her, nuzzling her from behind.

“You know I can’t,” Rina said. “There’s more to be done here, and I would not be very useful in setting up the base camp.” She closed down her opening as she felt his member trying to penetrate. “I will try to join you after the drilling is underway.”

She felt herself relax and flow as he stroked her sides.

#

The Indigo left, carrying the dozens of engineers and crew required to set up the great drill under the cap. The massive new drillhead was based on the diamond-studded metal ones the gods had left for rock drilling, but made of local ceram which was hard enough to drill rapidly through the ice above, boring a tunnel wide enough for a ship. She had to put down one revolt, an upper-caste guard family who sensed opportunity in the changes. Her guardsman took care of it after her spies reported the treasonous plan. More executions, then peace returned.

Months went by as the base camp was built, drilled into the underside of the cap. The drill rig was set up, and drilling began.

Business was booming for families she favored, and new factories and shipyards employed more of the lower castes who had survived on the Temple dole for ages. Most of the patrician families who had opposed her reforms stopped speaking against her as the money rolled in.

She spent more time at the Temple, questioning her scholars about the world above the cap. The grizzled old priest she had elevated to Magister, Edard, led her to the original library of Tapes and the ancient equipment that played them for transcription to understandable frequencies. He showed her how to set the equipment up to listen to them directly, then stood back as she tried to remember what sounds to make in what order.

“Let me help you,” he said. His markings showed respectful amusement. “You understand the gods created us by mixing cousins from their seas with their own form, so that we would have their brains and hands so we could run the equipment combined with the aquatic form we needed to survive?”

“Yes, every educated person knows that. I want more information on their world, and what we can expect to find beyond the cap.”

“For that, we already have volumes of scholarly writings based on clues in the Tapes. Here, for example, is Hykon’s treatise, ‘Fifteen Chapters About Earth.’ He is one of the few scholars who cited where each one of his observations came from on the Tapes, so he wasn’t just confabulating like the others. Well, mostly.”

“So I should listen to this one?”

“I would suggest that to start. He hints at what he can’t prove, and you can explore the subjects you’re most interested in by referencing the original passages in the Tapes. You can ask me for more help when you need it. I would warn you not to talk to the other priests, since they are an argumentative lot. They will only promote their pet theories. I say you are better off listening to the original sources.”

For weeks, she spent all the hours she could spare at the Temple. The Elder Tapes were a puzzle that appealed mostly to men, but she could see the attraction, the mysteries on mysteries, with understanding just out of reach. Shadows of the great knowledge of the gods, with more hints and infuriating omissions than facts.

She swam up from a reverie while a tape played in the background. It hit her—this one was surely a children’s story. The villain, some sort of furred animal, threatened the young heroine who was named for her brightly colored headpiece. Why was this left as one of their primary sources about their origin and purpose? It made no sense. Perhaps the gods had not planned to leave them. Perhaps it was an … accident. She was more certain than ever that everything in the Tapes was a story—not literally true, not organized to provide practical information, but just to lead the listeners through a false experience that only mimicked reality. It explained a great deal.

She sought out Edard. “I find it hard to believe the Tapes are more than a tiny part of the records the gods should have left us.”

Edard stroked his chin and looked thoughtful. “That was the focus of the first Schism,” he said, turning toward the translation console. “The Temple was founded on the Tapes we know. The heretics said there were others, but if there were, they were sealed in the catacombs beneath the Temple buildings, which are taboo—entering them is death. Those who have tried to go there, died.”

“Do you have records of those times? Why do we not have better records of our own history?”

“Every Magister has erased some records of his predecessor. The fate of those who wrote about their own times has been grim. Many of the scribes who tried to save old documents were executed, others imprisoned and beaten. The curious did not survive long.”

“But we must know everything we can know about the past. We are risking all to find the gods, and every clue they may have left us is important.” She widened her pupils to emphasize her will.

Edard nodded. “I understand, Highest. If we want to know more about the gods, we can’t be too afraid of their wrath. And they showed no sign of anger when we stopped worshipping them.” He stroked his chin again and hummed. “The main door to the catacombs has been sealed for ages, and there would be questions if it were disturbed. But there is another way—a back door which is rumored to exist. If you were to explore it on your own, I would not know and would not have to explain if asked. If such a place existed, it would be in the deepest basement furthest from the entrance. Anyone who went exploring there might find something they wished to forget.”

#

The lights in the Temple basement were dim, and the last hall was completely dark. It was strange now doing anything without her aides at her side, but Edard was a wise and loyal man, and she appreciated his hint that only by going alone could she control the proper interpretation of any records she might find—or suppress them entirely. She had brought some simple tools, and her headlights were enough to see the end of the hall as she approached.

The door was painted metal, with a wheel in the center. She tried moving the wheel first one way, then the other, but it didn’t budge. She used the hammer on one of the spokes of the wheel, and it moved slightly, then more as she hammered steadily. The wheel spun, and the door opened a crack, releasing a bubble of gas. When that had cleared, she was able to open the door all the way and enter the room beyond.

There was a fog of settled particles near the floor which she had disturbed enough to lower visibility. She found a light switch—she pushed it, and blinding blue light filled the cavity beyond from ceiling panels. She waited until her eyes adjusted, then moved down the shaft beyond to the floor below and found another light switch.

The room was enormous. The far walls were only dimly visible, with openings leading away from all sides. She looked down and realized what she had thought was a pile of sticks below her was a skeleton. The skull next to it looked alien to her. She shivered and looked to be sure the door was still open.

#

She explored the catacombs for hours, finding more skeletons. Shelves lined the walls, layered in organic ooze which she quickly learned not to disturb after her first approach raised a choking cloud. There were raised flat surfaces with dark ceramic sheets held above them on extensible arms. A side chamber held a console with a glowing amber ring. When she pushed it, the console lit up with complex lines and symbols, some of which looked familiar from the ancient machine controls. Then a voice spoke as the screen became a window into a different, brilliantly colored world.

“Welcome, workers!” The screen showed a creature with its mouth moving out of synch with the words. The creature’s face was dark brown and had some kind ofa white crest, with familiar dark eyes. His body was covered with red material. Behind it was a scene of dark green plants—and a blue emptiness above. Intense light flooded the space beyond the creature.

“We appreciate your service. Our mission is to gather data and explore the possibilities for human colonization of cold oceanic moons, which we now know are common in the universe. You will find your duty instructions in your augs. Europa Under has limited data service due to the magnetic storms and saltwater layers, but we have stored plenty of books and recordings. Please access the menus using the gestural controls.” The screen went dark.

She gathered ‘augs’ were some sort of data storage device. There must have been a time when everyone had one and depended on them for communication. ‘Gestural’? She tried touching the console. She tried every gesture and touch she could think of, but there was no response. After an hour, she was frustrated and hungry, so she made her way back to the entrance and closed the door with some difficulty.

The next day when she returned, the lights were dimmer, and the console had gone dark. She pushed the darkened ring again, but nothing happened. Whatever source powered the catacombs was limited, and she had taxed it too much.

But she had confirmed some of her speculations: the gods were only human, and had created the people in their own image, only different in being adapted to the watery environment of the Sea. The gods dwelled in a gaseous environment under a blue sky. And the Sun bathed them in light and warmth.

Somewhere above the cap, the Earth and Sun awaited. The mystery of what had happened to the gods compelled her to continue.

#

She had set her people to work on the problem of survival in the likely hostile environment above the cap. They would have to carry pressurized water to breathe, and be protected from the predicted absence of water (which the priests called ‘vacuum’ in their writings—what she had thought was a religious fiction, the absence of everything!)

A year went by as the tunnel work continued. Her shipyard built the first ship designed to venture beyond the cap—a sealed ceram shell with grippers forward and wheels underneath which could cross the hypothesized ice surface above it. It was already known that everything weighed more in the upper levels below the cap, and some thought the pull of gravity would be even higher above it, while others thought everything would be weightless beyond it. This did not make sense to Rina, since the stories made it clear that gravity was everywhere and went through everything. One story made the point that everything in outer space was always falling, and the planets were themselves falling around the Sun, but so fast they fell sideways and never fell in. She tried to understand this, but the references in the Commentaries glossed over the matter.

#

One day, she was in her bath when a messenger arrived.

“The Indigo has been spotted circling down from on high,” the lower-caste male reported. “Arrival is expected within the hour.”

Rina dismissed him and got ready to go to the docks. She was escorted by guardsmen, not so much because she was afraid of attack, but to remind people of her status.

The Indigo had tied up at the dock by the time she reached it. The long platform between the rows of flotation chambers held dozens of sleeping harnesses and boxes housing the cargo and the electrolytic gas generators, with hydrogen going to one set of chambers and oxygen to the other. Batteries under the deck stored the power needed to run the ship, and propellers behind pushed it through the water. Cowlings front and rear streamlined the platform. The ship could go as fast as anyone could swim, and keep going all night and all day while the crew were strapped on. Forward, a wheel controlled the rudders and lift wings that steered the ship.

She heard Joss before she could pick him out from the others on the deck. He ululated greetings, a triumphant sound as he swam toward her.

“We have succeeded, my love. The tunnel is nearing the surface. The expeditions to the surface can start in just days—so I’ve come back to collect you and your scientists.” They embraced.

“I’ll notify them we leave tomorrow. Let the stevedores load up supplies. Meanwhile, come back with me to the palace. Get a good rest.”

#

The Indigo set off again, this time with Rina strapped in next to Joss at the helm. They climbed under power and penetrated the first saline discontinuity after less than an hour. The water grew colder, and Rina and other passengers took refuge from the cold in the shelter aft. Hours passed, then they rose through another discontinuity, and soon, the featureless dark overhead resolved into a lumpy ceiling, with the camp buildings hung from it. The lights of the camp were visible through the murk, and as they slowed and closed on the dock, crewmen unstrapped and swam out to tie up the ship.

Rina led the passengers out of the shelter. It was very cold, but they had enjoyed warm broth earlier and she found her chills bearable. The lowered pressure had made itself felt in burps and other grumblings from her body, but nothing seemed amiss. Across from the dock, the buildings tethered to the ice above were brightly lit, and the passengers streamed down the dock to the open doors.

Inside, it was warmer, and when Joss came in last and arrived at her side, the chief engineer reported proudly. “We are making great progress. The first layer of ice was soft and easily melted, ground into slush, and carried out by conveyer.” He emitted an echo picture of the drillface. “The ice temperature dropped quickly, though, and the ice was much harder as we proceeded. But now, we see more rocks and cracks since we appear to be nearing the surface.”

Joss nudged Rina and said, “Is there any update on how much longer until we reach the surface?”

The engineer paused. “Progress is slow, and we have to be more careful. But I’d say days.”

#

Days passed. Rina and Joss toured the drill site, but the engineer refused to let them ride the rope conveyer in to see the drillface. “Way too dangerous,” he said. “The ice is shifting and could move at any time. We have installed a ceram lining as we drill, but we can’t risk losing the Highest in an accident.”

On the third day, a dim glow was sighted as the tunnel neared the surface, and in hours, the drilling was stopped. The surface expeditionary ship was readied and waiting at the tunnel mouth for launching upward. Joss captained, and Rina rode by his side. The tunneling equipment had been removed to leave room for the ship, which was almost as wide as the tunnel.

When they reached the top, the front window showed the last layer of fissured, dirty ice, but the light coming through the ice was blinding. The heated scoop dug into it, and soon they heard a rumble as the wall of ice gave way—and the ship pushed out of the tunnel in a flood of water and ice chunks, teetering at an angle before coming down to rest on its wheels.

“Best move before the water freezes,” Joss said, starting the forward motors to drive them away from the pool of water freezing around them. The front window showed a plain of white and pink ice, and an almost-black sky above. So this is the surface.

Joss turned the wheel, and the landscape in front of them moved sideways. And there it is. The pinpoint of unbearable brightness in the sky had to be the Sun. Everyone was silent and disappointed. The sky was otherwise dark and empty. Where was the Earth, the Stars, the life? And then the ship turned further, and the edge of an enormous banded globe appeared on the left. Rina gasped—it was beautiful! Was that Earth? But it could not be …

Joss turned to address the people in the ship. “Our protocol says we should turn back now. The tunnel entrance is freezing over. Highest, what is your order?”

“We’ll have to go back as planned and return only when we have a way of keeping the tunnel entrance clear. That means heaters must be installed.”

Joss nodded and turned back.

#

The scholars ran with their new data. The great globe they had seen in the sky was said to be ‘Jupiter,’ perfectly described in one of the Tapes as the closest planet to Europa. Earth was likely too close to the Sun to see in the glare of the Sun’s brilliance, and their eyes could not be focused in that direction without damage. The stars? They were pinpoints that only became visible when the Sun was not in the sky. Her understanding of the world outside the Sea was becoming clearer, and more depressing.

Gravity was very strong on the surface, and the need to carry their water environment with them made lifting a ship off the surface enormously difficult. The vacuum meant there was no buoyancy or familiar currents to use. Some scholars doubted it would ever be possible. The project to get to Earth was going to take everything they had, and more.

Meanwhile, the people grumbled about the hard work and long hours. Food rations had been cut, and workers were given little time to enjoy their traditional pastimes. Rina had her secret police arrest and punish all who were reported for negativity, but still, the whispers grew louder. Production dropped as the workers lost interest, and commerce slowed as there was little to buy since most production had been diverted to the space mission.

The tunnel had been reinforced and heaters installed to keep the entrance from freezing again. But what was the point? The spaceship had been sent out on expeditions and collected more observations from the surface, but there appeared to be no reason to stay—nothing up there was useful, and supplying energy and water to the surface for a permanent base would be difficult. Plans to launch ships into the sky above were far beyond their current abilities.

Rina was stymied. She had put everything she and her people had into following her vision, and it was a dead end. The old gods, if they still existed, were out of their reach for a very long time.

#

“Rina,” Joss said, nudging her awake. “We need to talk.”

Joss had returned from another trip to the tunnel, where the dispirited team had taken to betting on the week they would be shut down.

Rina opened her eyes. “What is it?”

“You must do something. The men are unhappy. The Families are conspiring to overthrow you. You’ve been depressed, and it shows.”

“It will simply take more time to get to Earth. We need to develop some way to lift our ships. The scholars have ideas.”

“Nothing practical in this lifetime. You must stand down and let people go back to normal life.”

She wouldn’t take this naysaying from most people, but Joss was her trusted man. “Do you have any suggestions? If I stop the project, I’ll lose face. It will all have been a waste.”

“At the very least, you need to ferret out the plots and get rid of the plotters. And release some production for normal uses. You promised the people a reward for their sacrifice and if it doesn’t appear soon, they will turn on you. The men are grumbling.”

Rina had already been considering her options, but she hated backing down. The next day, she gathered her aides for her next steps.

“We’re going to have to build larger ships and expand the tunnel. We’ve learned a lot, and now there will be a pause while we prepare for a larger expedition. We won’t spend as rapidly, but the mission will continue. And meanwhile, the Families working against me need another lesson in obedience.”

Her security aide pushed forward. “You haven’t responded to my reports on traitorous activities … can I implement my proposal?”

“Just take out the followers of Kai for now. That will quiet the others.”

“Yes, Highest.”

“And as for the rest of you—prepare a new budget for the longer term. Release resources for the civilian markets and go to half current production for the Mission.” She motioned to the chief engineer to come forward. “Expand the tunnel to twice its width and prepare a design for a ramp to the surface.”

“As you command, Highest. We have already done some design work and commissioned new lining cerams.”

#

The arrests of the most obvious plotters kept the rest quiet. Months went by. She kept her crews busy and sent the expeditionary ships further out on the surface to gather more reports. Scholars and engineers worked together on new devices to propel the ships upward from the surface with chemical energy—calling them rockets, echoing one of those words from the stories. The engineers threw themselves into the work, knowing it was their last hope.

Her people settled into the new routine, satisfied by the increased rations. The following year, rockets were tested on the surface. One exploded, burning most of the crew alive and leaving the rest to die of explosive decompression before they could be rescued. Rina held a solemn ceremony honoring their sacrifice. Her popularity rose.

She was holding an evening court hearing when a messenger rushed in, gasping. “The chief engineer … is on his way from the port. It’s an emergency!”

Rina gracefully dismissed the parties to a dispute about unpaid debts. It wouldn’t do to let them see her upset. The chief engineer arrived soon after.

“Highest, there is a serious problem with the widening project. We have just started on it, and the tunnel walls have been collapsing inward as soon as we remove the old liner. Before we can carve out the sidewall to install the new liner, more ice has squeezed in to fill the space. Fissures have started to open up around the drilling site. The whole area is becoming unstable.”

Rina controlled her anger. “What would you suggest we do?”

“Abandon the site and move the base to a more stable area.”

“How long will that take?”

“I’d say two months to move the base, faster if you can give us more transport.”

#

Days later, Rina’s world changed as the ice above them shifted. A frantic messenger reported that the tunnel to the surface had collapsed before the base camp could be moved, and the stressed ice crust cracked. His ship had been nearly destroyed by the pressure waves as bright cracks opened above, and rocks rained down on them as the submerging ice melted in the warmer water below.

The rock falls damaged the Temple and many of the other buildings. Thousands died.

Rina shut herself up in the undamaged wing of the Palace and refused to see anyone. Joss had been at sea when the sky fell, and as the days went by and his ship failed to return, Rina lost hope. She began to drug herself to escape her shame and pain. The people were quick to blame her for the disaster—nearly every Family had lost members, and many homes and workshops had been destroyed. When she failed to appear to lead the rescue efforts or visit the injured, the public mood turned ugly.

Rina’s younger sister, Lira, persuaded her to meet with a delegation of her political allies in the Palace hearing room.

“Highest, what are you going to do? Your projects have exhausted us, and now we are ruined. People died, and the survivors are going hungry. It is going to take years to rebuild.”

Rina closed her eyes and spoke wearily. “I was right, but I pushed us too far, too fast. We’ll build up again, and next time choose a site far away from our settlements.” Her voice strengthened. “God is testing us, and we should not give up.”

“The people believe your new god has failed. They want to sacrifice to the old gods and return to the rituals that kept us safe.”

“You know we can’t go back. The power plants are failing, and we have no way to repair them.”

This was news to some in the delegation. An older cousin pushed forward and said, “Then it’s all the more necessary to stop this space heresy. Put the engineers to work fixing the power plants.”

Rina sighed. Perhaps if she had taken the time to persuade the Family heads that they faced extinction unless something was done … but it was too late now.

The delegation left, and Rina only discovered the next day that they had decided to depose her. When her own guards came to arrest her, she was asleep. They beat her until she was unconscious while her servants looked on.

Rina opened her eyes. She had been dragged in a net to the same spot in Temple Square where Wingren had been executed. She was not surprised to see Wingren’s family and the other conservatives in the front ranks, but a surge of anger went through her when she realized her own sister Lira was at the head of the mob, surrounded by courtiers.

Lira turned to the crowd behind her and spoke. “It is unanimous—Rina has dishonored the gods and been judged. Her record will be expunged and any talk of going beyond the cap will be punished by death. All will be returned to what it was before she ruined us, and the gods will forgive us and restore our old life. I, the Highest, decree it.”

Rina tried to speak, but nothing came out. She struggled in the net. Lira looked down at her.

“Let me speak,” Rina whispered.

“I think not. You’ve already done enough damage,” Lira whispered back, then shouted, “Guards, forward. Do your duty, and make it quick.”

The crowd roared approval, and guards battered Rina’s body. It was over in minutes.

#

EARTH, 2353

In the Orbital Telescope data center, a terminal chimed to signal an anomaly. Astronomer Anders Balewa checked the flagged report on his screen and noted the latest photos, compared side-by-side with last month’s.

“Jen, have you seen this? Europa survey, south end of Conamara Chaos.”

“Checking … oh, I see. New terrain! We should send out an alert.”

“Get that out now with the location and new photos. Add a line saying we’ll be issuing a more complete report tomorrow.”

“Sure thing … hah, I just got a request for more data from the Australians.”

Anders pulled up some high-res images of the area and the infrared scans. “See anything else odd about this?”

Jen looked over his shoulder. “Huh. Those look like tracks.”

Anders magnified the area. “Notice the tracks parallel this pressure ridge, then cross it as soon as it’s less steep. They all start from this unusually warm area next to the new terrain.”

#

The great auditorium was packed and buzzing with conversation. Millions watched remotely as the Speaker took the podium.

“The Europa settlement was abandoned at the start of the Drone War. It took two centuries to restore our capacity to get into space, and the genadapted workers on Europa were assumed to have died without resupply, since all communications were lost. The trails above the base location and the activity there almost certainly prove they survived.”

The auditorium fell silent, and the slide behind the Speaker changed.

“In light of this new evidence, we propose a mission to find and assist the survivors. We owe it to the original volunteers to help their descendants. The planned expedition to Mars is being re-targeted, and a good launch window opens up early next year …”

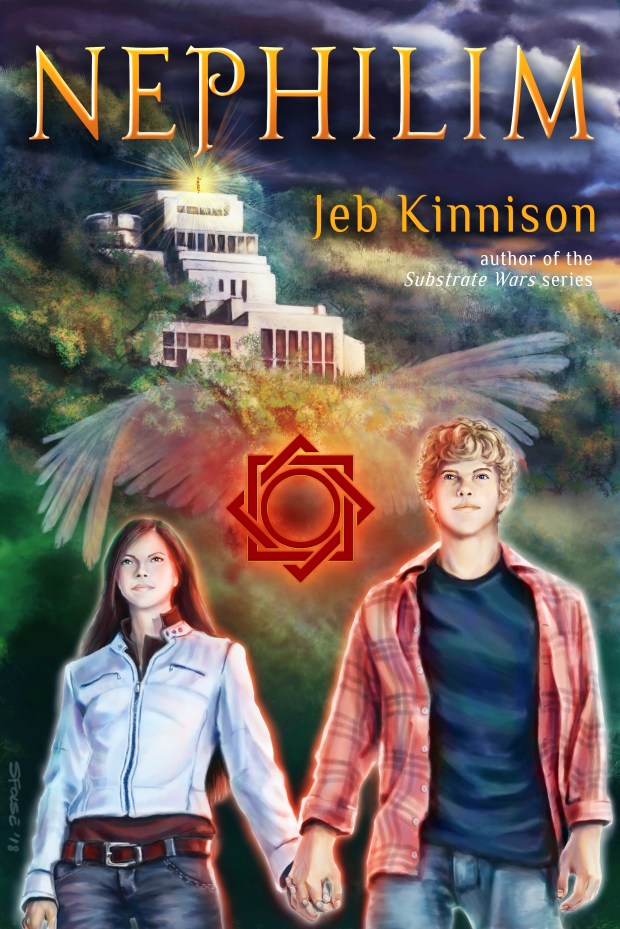

END SUNWARD by Jeb Kinnison

You must be logged in to post a comment.