Watched Star Trek Beyond at the local theater minus 3D or extended screens. Entertaining and a bit of a throwback to a typical TOS episode: contrived situation, bad science, attempts to make a social point, plenty of interpersonal character-building.

The first scenes present a tired Captain Kirk after a few years of their “five-year mission,” playing diplomat to bring a symbolic gift to a paranoid species who see it only as a trap. Kirk wonders what it’s all for, then the ship picks up a distress call and rescues a survivor who claims her people have crashed on a planet inside a nearly-impenetrable nebula (your usual SF-movie-cliche dense asteroid belt with constant collisions, which wouldn’t last a hundred years in that form.)

The ship returns to the new Starbase Yorktown, an asteroid-scale glass bauble threaded across with bridges lined with skyscrapers projecting at all angles — artificial gravity permits this rather impractical and fragile city-station, which is inhabited by a multicultural, multispecies cross-section of the Federation. It is decided that the Enterprise will undertake the rescue mission since they have the most advanced equipment for penetrating the nebula. Kirk discusses his ennui and future career path with Commodore Paris (played by the excellent Shohreh Aghdashloo, recently of The Expanse), who advises him that some dissatisfaction with ship life is normal for a captain and they can discuss his transfer to a desk job as Rear Admiral after the rescue mission. Meanwhile, Spock is considering leaving Starfleet to take up responsibilities on New Vulcan now that Old Spock has died, and his lack of commitment has created a rift between him and Uhura. The theme — which will be later reinforced by the villain Krall’s motivation — is being stuck with the job you have while feeling drawn to another responsibility you think you want to pursue.

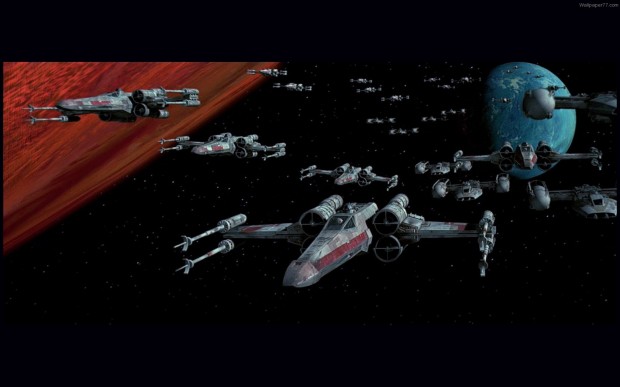

After the Enterprise penetrates the nebula and approaches the planet, they are attacked by swarms of metallic shard-ships that penetrate the shields* and embed themselves in the hull. The ship is disabled and the saucer section is separated and crashes, while most of the crew have escaped in pods which land in the same area.

Scottie meets a major new character, the alien Jaylah, whose alien-ness is signalled by white makeup and stripes on an otherwise completely human face. She has escaped from Krall’s prison camp where spacefarers captured by Krull are held to labor and keep him alive — he feeds on them for eternal life. Coincidentally (!) she lives in the crashed USS Franklin, which she has been gradually repairing — her dream is to escape the planet, and she wants Scottie to help her fix the Franklin so she can.

[spoilers follow…]

Conventional escape plot follows. The Franklin happens to have a motorcycle aboard which Kirk uses to conduct a distraction raid on the camp while the others spring the prisoners. Krall has obtained the McGuffin — the ancient artifact Kirk had tried to give the paranoid species in the first scene, which turns out to be the key to an advanced nanoweapon Krall intends to use to destroy Starbase Yorktown. Krall leaves to attack Starbase Yorktown with his swarm-ships and our heroes follow in the restored Franklin.

Naturally there’s lots of hand-to-hand combat and inaccurate phaser fire, chases, and humor. Kaylah is a fresh new character and had some good lines at the expense of Federation culture, which she’s studied in the Franklin’s data stores.

Our heroes discover the swarm ships are controlled by an FM radio signal, and start jamming it with FM broadcast of the same Beastie Boys song the young Kirk played when he had “borrowed” and crashed a Corvette in reboot movie #1. The swarm ships crash into each other and burn. The idea that an advanced alien mining system would be controlled by noise-sensitive FM radio easily disrupted by another signal is pretty unlikely, after we were already asked to believe no Federation vessel could deal with a swarm of projectiles, so we have to give the science advising on the script a big FAIL.

Krall, it turns out, was actually the captain of the Franklin when it crash-landed over a hundred years earlier, and he discovered an alien technology that allowed him to extend his life at the expense of others. His motivation? As an ex-soldier from the pre-Federation era when Earth was at war, he felt abandoned and wanted to return war and chaos to the overly-pacifist Federation. This is intended to parallel Kirk and Spock’s search for meaning — but doesn’t make any sense. He claims he was abandoned by the Federation, but he’s well aware the nebula is impenetrable and the Federation doesn’t even know what happened to the Franklin. It is presumed his mind has been warped by the alien life-extending technology, but it’s barely touched on in hopes you won’t notice it’s implausible.

When the same motorcycle model as Kirk’s dad used was found on the Franklin, I was sure the writers were going to contrive some explanation that explained that it was in fact George Kirk’s. Good thing they realized this was a step too far in symbolic coincidences, but the writers still worked in some unconvincing thematic parallels. That the motorcycle and ship still worked over a hundred years after a crash landing also pushed credibility.

Meanwhile, our theme is served because both Kirk and Spock recognize that their team is worth sticking with and that they’re doing valuable work right where they are, on a team of friends who can count on each other in crisis. This is a bit formulaic — be happy with what you have! I can see the motivational poster now.

So while I enjoyed the movie, it was like an episode of ToS – not bad, try again. A bit more substance to the story — and a more credible bad guy — would have helped a lot. Hire real writers, a military science advisor, and have Pegg add humor as needed; this outing is just adequate.

This is another recent big-bucks production showing the increasing influence of overseas markets, notably China, on story depth. Director Justin Lin comes off the successful Fast and Furious franchise. These films featured a thin layer of lowest-common-denominator character development over hours of car chases and macho posturing, so crossed language and cultural barriers easily as popcorn cinema. As Lin explains in a Verge interview:

“Before I said yes, I had to really understand what we were going to do, even on a thematic level. I thought, okay, it’s going to be 50 years [since the show started]. It would be great if we can somehow come up with a journey for these characters to deconstruct Trek, to deconstruct a lot of the ideals of the Federation. By doing that, maybe by the end, we can reaffirm why there is so much passion and so much love for this franchise.”

“It was like, ‘Let’s ask some questions that haven’t been asked before,'” explains Pegg, particularly when it came to the universe’s United Federation of Planets — perhaps the biggest symbol of the show’s utopian ideals. “It felt good to question whether they weren’t just a version of the Borg in a way. Whether they were just a force of assimilation, not a force of collectivism and goodness.”

For Lin, deconstructing Star Trek started with an idea that he admits was rather literal: taking the Enterprise apart piece by piece in one of the film’s opening set pieces. “Simon was like, ‘You can’t destroy the Enterprise and you can’t do it in the end of the first act. It has to be the end of the movie!'” Lin laughs. “That was our first meeting. We walked out and I think all of us were like, ‘I don’t want to work on this movie. What’s going on?'”

“We call it The Longest Day,” Pegg smiles. “We were in this room at the SoHo Hotel, just talking for 16 hours and we didn’t seem to be getting anywhere. But it was a great way to establish that all of us really wanted to make the best film we could.”

But as the team started writing the script — Pegg was still shooting Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation, so the trio would sometimes be working in different time zones as the calendar raced toward production — they found themselves looking to political events, where the first signs of the Brexit movement and the start of the US presidential race resonated with the story they wanted to tell. “It was all bubbling up then, with the Scottish referendum and various acts of separatism around the world,” Pegg explains. “Trump talking about building a wall between here and Mexico. This sort of rampant xenophobia that seemed to be reestablishing itself.”

In the finished film those concepts manifest in the form of Idris Elba’s Krall. A former soldier intent on stopping the Federation’s spread across the galaxy, Krall comes across ideologically as the anti-Roddenberry. He preaches isolationism where the Federation wants to expand and include all; he rejects peace and sees solutions only in military strength. It’s not subtle allegory, but it works, and as the crew of the Enterprise recover, they learn the only way they will be able to defeat Krall is to come together and work as a whole — a literal depiction of Roddenberry’s multicultural future.

“We liked the idea of old god versus new,” says Pegg. “Of narrow-minded thinking, or fear of collectivism, versus the Federation model, which is to embrace and expand in a non-aggressive way. That seemed like the obvious thing to do for this 50th anniversary iteration of the story.” It turns the film into a thematic proof, making the case for the original show’s vision over the course of its running time.

Star Trek Beyond is an entry in a successful series of blockbuster movies, so of course everything eventually resolves to allow sequels to keep coming down the line. (In fact, Paramount’s already green-lit the next installment.) But by creating a movie that feels more like an episode of the original show, with its five-year mission and themes intact, Lin and his writers have also performed a sort of soft reboot. And to Pegg, the closer it feels to the television series, the better.

“When we spoke about [writing Beyond], it was, ‘Let’s make it as if an episode of the original series had been injected with gamma radiation,'” he says. “The crew happen upon a mysterious planet. They’re on the surface. They meet an adversary. They learn a lesson. It’s what the original series episodes were constituted by, but with the trappings of a gigantic, summer blockbuster. Which is what the movies always were, really.”

From this interview we see that the script was rushed and the story thrown together by writers unfamiliar with science fiction and interested in simplifying the message to fit it back into the TV format of TOS. Like Tomorrowland, the movie fails to explore its subtler thematic implications because most screen time goes to hand-to-hand fighting, chases, motorcycle stunts, and high-school-level relationship interaction. The new Spock has Uhura as a love interest apparently for years when they break up because he is thinking of heading back to New Vulcan. New Spock is often emotionally out-of-control, a plot ploy that is only valuable if rarely used.

So — enjoyable light entertainment, but giving up on the opportunity to explore larger issues seen in even TOS plots, and even more in later DS9 and TNG episodes.

—

* – What exactly are shields good for if they can’t stop impacting objects? Has the Federation and its many contributing civilizations never encountered swarming weapons before?

Trailer #1:

—

More on pop culture:

“Tomorrowland”: Tragic Misfire

Weaponized AI: My Experience in AI

Fear is the Mindkiller

The Justice is Too Damn High! – Gawker, the High Cost of Litigation, and The Weapon Shops of Isher

Kirkus Reviews “Shrivers: The Substrate Wars 3”

Death by HR: How Affirmative Action Cripples Organizations

Death by HR: How Affirmative Action Cripples Organizations

You must be logged in to post a comment.