View of Provo from Marriott

This is my AAR (After Action report) on LTUE (Life, the Universe, and Everything) in Provo, a weekend starting February 15th, 2018.

LTUE is officially a “symposium,” not a con. The emphasis is on writers and prospective writers discussing all aspects of writing SF&F, so there is little cosplay or general game and comic book fandom material. The location at the Marriott conference center in Provo is a mile from BYU and at the center of the LDS-Mormon intellectual world, such as it is. I knew Provo was majority Mormon, but when I checked I discovered an astounding 88% of the city’s population is LDS-affiliated. But Mormons are disproportionately readers and writers of SF&F, as traditionally they are raised to value education and often encouraged to write journals.

Provo late afternoon

In the photo above taken from our room, you can see the ‘Y’ on the mountainside overlooking BYU’s campus. The ‘Y’ is made of stone and a popular hiking destination.

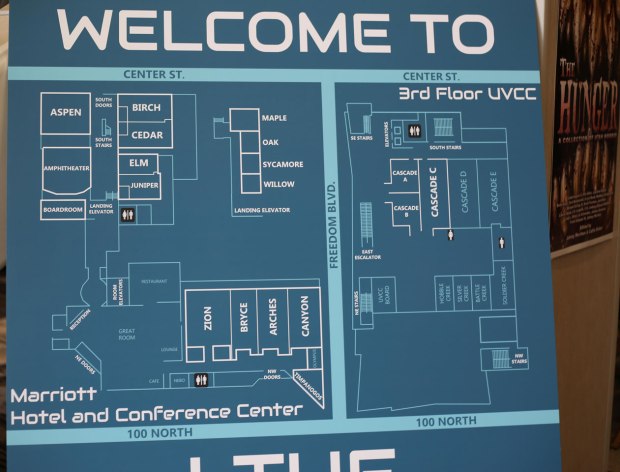

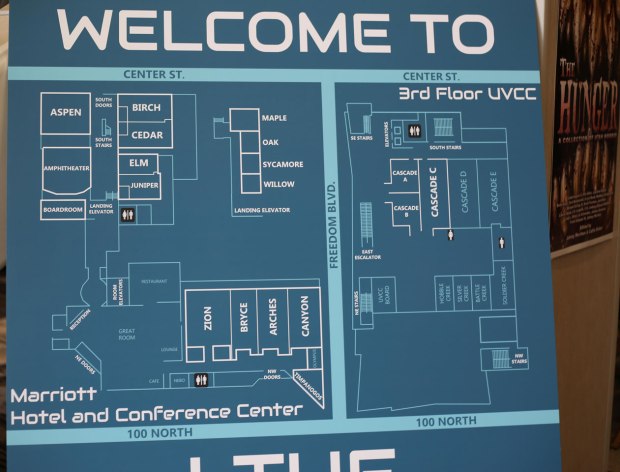

LTUE conference room map

Panels and presentations were scheduled from 9 AM to 6 PM Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. I had registered last year, then applied to be a Guest. When they put me on three panels, I gave my registration to my husband Paul, who has just retired so is able to travel with me more often. Of course Registration had no record of that, but we straightened it out quickly.

LTUE: Registration

LTUE hall

The LibertyCon contingent was well-represented, with local writers Larry Correia and Brad Torgersen, and Sarah Hoyt in from Colorado. Baen did its roadshow and the infamous Lawdog attended. While I met Larry briefly at LibertyCon two years back, I saw a lot more of him and his charming wife Bridget this time. We had listened to the audiobook of “Tom Stranger, Interdimensional Insurance Agent” (written by Larry, read by Adam Baldwin) on the drive up. As Larry’s media empire has grown and the movie options for some of his worlds are pending, it’s kind of a thrill that he now knows who I am and lets me hug him (his excuse being his arm was injured and couldn’t take too many handshakes.)

“Lawdog” and Larry Correia

It’s also nice to hang out with Dorothy and Peter, though they were under the weather some (in Dorothy’s case, she had a touch of altitude sickness. Provo’s at 4400 feet, and I didn’t sleep well, either.)

Peter and Dorothy Grant

LTUE: Marriott lobby

LTUE: Art in the hall

And it was great to touch base with Sarah Hoyt (and Dan, who I’d never met!) Jonathan La Force was as usual a forceful presence on panels and at the BBQ, making much of the great food for the post-LTUE party on Saturday night.

Sarah Hoyt and Jonathan La Force

There were relatively small vendor and game rooms. One of the few complaints we all had is that some of the conference rooms were way too hot. But on the whole everything went very smoothly and most attendees say they will return.

LTUE: Game room

LTUE: Game room

LTUE: Game room

LTUE: Vendor room

LTUE: Xchyler book booth

Panels were wide-ranging and I didn’t get to go to enough of them. The schedule is here.

The first panel I was on was “Making Money.” We discussed all matters currency, though I never got to mention Charlie Stross’s “slow money.” Fellow panelists were: L. E. Modesitt, Jr., Roger Bourke White, Jr., Bob Defendi, and Alicia McIntire. This was my first encounter with L. E. Modesitt, an extremely impressive person who may actually know more than I do about many things. Roger Bourke White is a fellow MIT grad (a senior when I was a freshman), so we compared notes. We ended up spending more time emphasizing that credible worlds will have a worked-out economic system, whether it is AIs and replicators, conventional price systems and money as we know it now, or barter and ad-hoc tokens — the check was invented in ancient Sumeria as a clay token exchangeable for a certain quantity of grain!

The next day I was on the first LGBTQ panel ever for LTUE, moderated by local fantasy author Michael Jensen. With fellow panelists J. Scott Bronson and Scott R. Parkin, we went over some of the historical broadening of SF&F from cardboard characters whose conventional characteristics were secondary to adventure and technology stories to more cultural and psychological varieties of speculative fiction. Since I have been reading SF&F since the mid-1960s looking for stories about “odd” types, I spent some time reminding the younger people in the audience that since the mid-1950s at least, SF&F was one of the earliest genres to explore stories of unconventional gender roles and sexualities, at first among aliens, then as acceptance grew, among human societies. Today’s emphasis on representation of oppressed groups may be overdoing it a bit, and we discussed the importance of fully-rounded characters — it is no longer especially interesting or ground-breaking to have LGBTQ characters, and all characters need to have their many facets presented for involving storytelling. Many audience members were there to find out how they could write these characters when they had not directly experienced being LGBTQ; the answer (in the current climate of Twitter mobbing) would be “very carefully.” But we all agreed that using empathy and passing your work by a few beta readers more closely involved to check for errors of tone or language would probably work well, especially when the story is not centered on uniquely LGBTQ experiences but includes them as part of more realistic and complex characters.

We went off to lunch at the Indian buffet next door to continue the discussion.

Post-panel lunch

Post-panel lunch

My last panel was “Well-Developed Political Systems: Who Got It Right?” moderated by Gordon Frye and featuring M. A. Nichols, Luke Peterson, and L. E. Modesitt, Jr. I was late because I had misread my schedule since I didn’t have my reading glasses, so first went to the wrong room across the street. Again I was mostly echoing Modesitt. Luke Peterson is extremely knowledgeable and I practically squeed when he recommended Albion’s Seed by David Fischer, one of the great books on US political attitudes and culture — I had just written it into my latest book in a discussion of where Mormons came from (answer: they are a cut-off and isolated branch of New England Puritanism, evolving in a separate cultural bubble after the Exodus from the Midwest around 1847.)

The last day I attended the hot and crowded panel, “Writing Battle Scenes” with Kal Spriggs moderating, with Gordon Frye, L. E. Modesitt, Jr., Larry Correia, and Brad R. Torgersen. This was a fun group, with two panelists confessing they don’t really love writing battles but Larry telling us he lives to write them. I’m in the “They’re necessary but I don’t dwell on it” camp myself, and if you don’t love them, you probably won’t do long ones well.

LTUE: Panel on writing battle scenes

LTUE: Panel on writing battle scenes

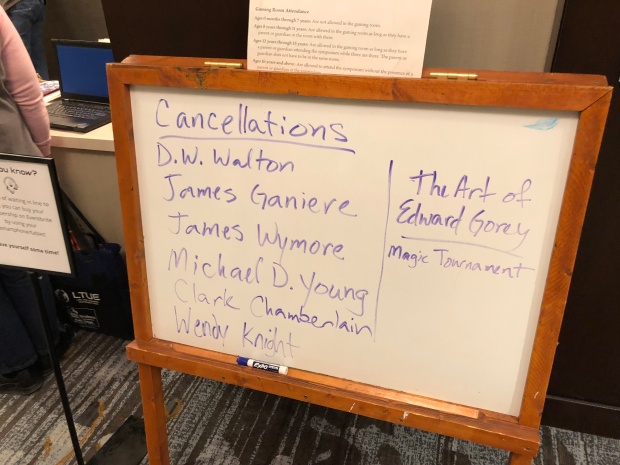

LTUE: Cancellations board

The “symposium” wound down Saturday night. We had reservations for the banquet but chose to go to the informal afterparty at the AirBNB next door where many of our friends had stayed. It was a group effort, with attendees pitching in to get the BBQ and supplies brought by Jonathan La Force in and ready. The presence of many children and families, and locals who hadn’t been able to attend LTUE, made it a great party. It must have been very interesting for Paul, who’s heard a lot about my imaginary writer friends and finally met them en masse.

LTUE: Afterparty

LTUE: Afterparty

LTUE: Afterparty

LTUE: Afterparty cooks

LTUE: Afterparty

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

2016 Worldcon / MidAmericon II Report

2016 LibertyCon Report

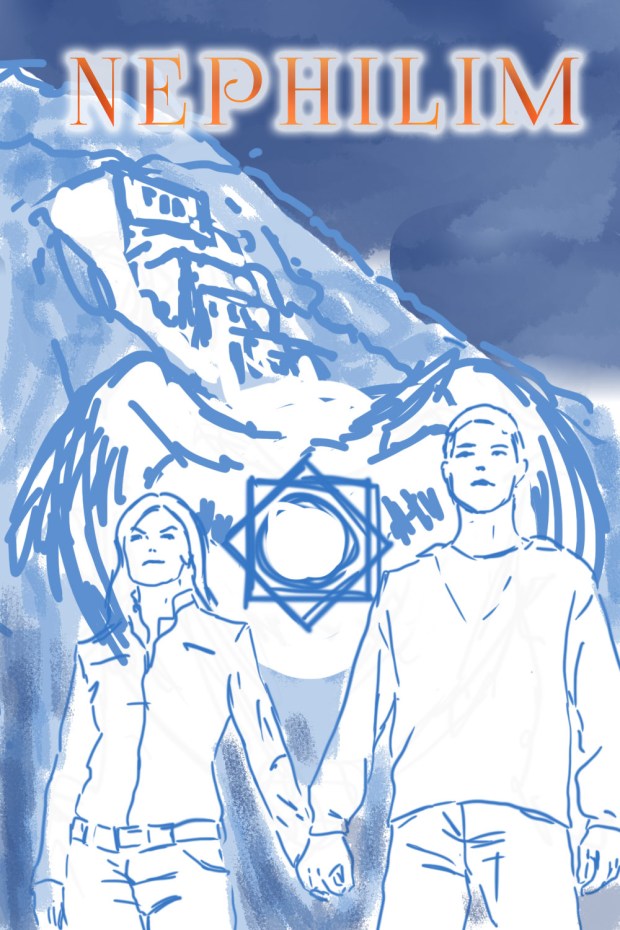

On the way back to Palm Springs, we stopped to see some of the sights featured in my latest book, Nephilim:

First we tried to find the Dream (also known as Relief) Mine, on a mountain overlooking Salem. There were two possible approaches and the one we tried was blocked by a security gate and “no trespassing” sign. Even though we couldn’t get very close to it, it was interesting seeing the countryside I had already written into fiction.

Near Dream / Relief Mine

Near Salem, UT

Valley view near Salem

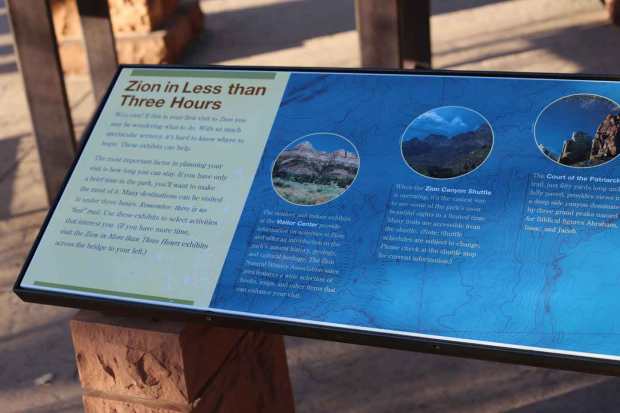

Then we checked into a motel near Zion National Park. The weather forecast was for a storm starting early AM, so instead of the planned trip into the park the next day, we decided to make an afternoon visit so we could leave before the onset of the storm the next day. We only had a few hours in the park, but the afternoon sun and blue skies made for some great views, and it was uncrowded — which was good since the main access road was half torn up with alternating one-way traffic.

Zion NP

River in Zion NP

Mule deer in Zion NP

Zion NP

Zion NP

Cactus in Zion NP

Zion, late afternoon

Zion NP

We left the park near sunset and had dinner at a terrific little Thai restaurant just outside the gate. Our table had a gorgeous view of the cliffs at sunset and a closer view of the road work and workers!

Zion NP: Thai place just outside gate

The next day we made good time through Las Vegas, where some scenes of Nephilim take place — the spirit driving Sara, Lailah, selects the Luxor as her headquarters, offhandedly noting that it felt good to have a pyramid of her own again.

Las Vegas: Strip from I-15

Las Vegas: Luxor from I-15

There was an hour-long backup near the California border at Primm, so after suffering through that we noted a similar backup on I-15 before LA and decided to take the back route through the Mohave reserve to Yucca Valley and home since the GPS said it would save over an hour; normally we wouldn’t because of the risk of having no cell service or road assistance in most of the area. But it was lovely and quiet as he storm hit and snow began to fall amongst the cactus and Joshua trees.

Mohave Reserve, Joshua trees

So the launch of Nephilim at LTUE went fairly well. One scarily intense fundamentalist Mormon man was unhappy, dropping by at the mass signing to tell me the Church does not support the idea of demonic possession. I pity the scared little girl he had in tow… and I understand why LDS authors keep their fantasy and SF safely away from any discussion of church doctrine. There are always holier-than-thou sorts waiting to find fault.

He hadn’t read the book, so he was unaware that it specifically makes that point — the angels Jared encounters (which the reader can choose to believe in or not, since an alternative explanation is also in the text) tell him he is free to choose. It’s Sara who is actually possessed, again by a spirit pretending to be from her Jewish heritage — but which might be something else entirely.

Nephilim

My story “Sunward” is in the upcoming “Planetary: Jupiter” anthology (republished by Tuscany Bay.) It’s a tale of lost colonists in Europa’s ocean yearning to return to the fabled planet of the gods. Their imperious queen mounts a space program at great cost…

My story “Sunward” is in the upcoming “Planetary: Jupiter” anthology (republished by Tuscany Bay.) It’s a tale of lost colonists in Europa’s ocean yearning to return to the fabled planet of the gods. Their imperious queen mounts a space program at great cost…

You must be logged in to post a comment.